With many fixated on the Biden debate meltdown and the SCOTUS Presidential immunity decision, another SCOTUS decision this session may have inadvertently created a new path for our political system to take. A path that could restore the trust of the American public in their government.

The decision--which strikes down the “Chevron Deference” rule that allowed the Executive branch to write the federal regulations associated to laws Congress passed--will realign the power dynamics between the three branches of government. The decision stripped the Executive branch of this rule making power, but the question of where this power will migrate to, is an open question. In today’s hyper-partisan environment, the Republicans hope, and the Democrats fear, this power will flow to the courts which are viewed as more friendly to the business interests than the health and safety of the public. But instead of returning a Gilded Age of jurist-prudence, we could take this opportunity to forage a path that would be more responsive to the complex needs of the 21st Century.

In the Loper Bright Enterprise v Raimondo decision, SCOTUS ruled that the Executive branch cannot write the technical regulations that are used to implement the broader laws Congress passes. The ruling is part of a legal effort by conservatives to end the “administrative state” by declaring that Congress has given the executive branch to much power to define and implement laws passed by Congress. Since 2022, SCOTUS has ruled twice to curb the EPA’s ability to enforce the Clean Waters and Clean Air Acts passed by Congress. Even the SCOTUS running to overturn the bump stock ban had more to do with limiting the administrative state than protecting the Second Amendment.

There are several New Deal/Great Society era SCOTUS decisions that still need to be struck down before the administrative state is declared dead. But with conservative groups scouring the land looking for ideal cases to bring before a sympathetic SCOTUS, it will only be a matter time before the executive administrative state is dead.

But will conservatives win the legal battles but lose the political war? While bureaucracies are never popular and there are many examples of bureaucratic overreach, the fact remains that the 21st Century—just like the 20th Century—is complicated. Contaminates from a watershed WILL leach into lakes and rivers used for drinking water, overfishing WILL result in no fish, criminals ARE printing 3-D guns, consumers WILL be scammed by predatory companies, et cetera. None of this will stop. What will stop is the executive branch ability to write regulations that can prevent these consequences.

Chief Justice John Roberts’ written decision suggests that the judiciary should be the arbitrator of the laws Congress passes. If so, will scientists and other subject matter experts be replaced with law clerks to evaluate evidence in complex cases? Will the federal judiciary create their own bureaucracy of experts pertaining to every conceivable issue that comes before them? Not only is that scenario unsustainable, it is also the epitome of unelected people deciding our fate.

How will the public react to a laissez faire corporate approach to the environment, the financial industry, health care, technology and every other aspect of contemporary life? We may hate bureaucrats, but we like clean water and safe food. Bureaucratic indifference is intolerable, but we also recognize there are powerful forces that will exploit their leverage over individuals—effectively denying them freedom and liberty—and these forces need to be contained by a government elected by the people.

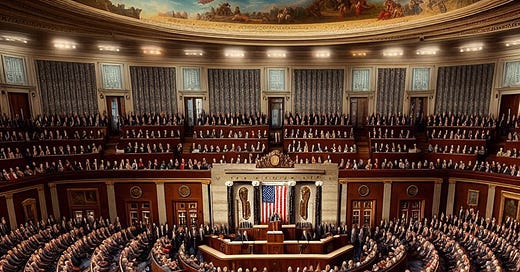

So, if the executive branch is not allowed to make highly technical regulations and the judiciary should not be making regulatory laws, that leaves Congress. LMAO, as we all recognize that Congress is too inept, corrupt, gridlocked and under resourced to undertake the task of writing specific regulatory rules required for sweeping legislation.

In pondering the question of how resolve complex disputes in a post-executive administrative state, we need to take into account our current political environment, which we know is horrible. We the people trust no one. We need to reshuffle our governmental institutions and begin anew. Ending the ability of the executive branch to make regulatory rules is only half a shuffle and, if left on its own, it leaves a large power vacuum to be filled by corporate interests. What we need —and fast—is an alternative power vacuum that will be more aligned with the citizens of the Republic.

Ideally this new “power vacuum” will have tenacles in all fifty states and not be viewed as a DC Darth Vader. It will also be responsive to local communities and follow the facts on the ground instead of a mountain of arcane regulations. (Something the courts and bureaucracies have in common.)

Fortunately, there is an entity that currently exists that theoretically meets these criteria but requires extensive reconstruction and reform. The best part is this reform: it will not require amending the US Constitution, which is a deal breaker in our hyper-partisan environment. Instead, a simple act of Congress can significantly increase the size of the House of Representative and shift the writing of regulatory rules and oversite to a newly revamped—and strengthened—Congress, while the Executive branch enforces the laws and regulations passed by Congress.

Our Constitutional framers always envisioned the size of the House would increase as the population grew and new states were added. The framers felt the “ideal” size of a Congressional District would be 30,000 voters, giving Representative a real sense of what their constituents’ needs were. The House continually grew in membership until 1930, when Congress—who has the power to dictate the size of the House--capped its size to the current 435 Representatives.

Of course, with more than 300 million people, it is not realistic to have 10,000 congressional seats representing 30,000 constituents each. But it is equally absurd to think that the current size of congressional districts—about 800,000 people—is small enough to address the real needs of district voters. The general argument for uncapping the House is that it will create a Congress that is more responsive to a smaller group of voters.

Experts feel the House can be expanded to about 1,200 members without any logistical challenges to accommodate a large body and having smaller districts THEORETICALLY mean members of the House would be more responsive to voters. But expansion, without additional reforms (like limiting big money in politics) and responsibilities, would still continue the status quo in the House--just with more members and staff. So, the solution to ending the political gridlock in Congress cannot simply be to create more politicians. But to change the power dynamics in Washington DC. (Ironically, it will be the current 435 members of the House that will be the most oppose to the expansion of Congress, because every member will lose the power and prestige of representing 800,000 people and will balk at diluting their powers by a factor of three.)

This is why there needs to be a far greater reason the expand the House than the potential for more responsive House. The power vacuum created by the Loper decision gives expand House new powers so they can fulfill their basic mission: To create laws for the betterment of their constituents.

In an expanded Congress, House Committees—some with as many as 100 members and their staff of subject matter experts—would develop the regulations that Congress customarily ceded to the Executive branch. When a local dispute arises between—say—an oil refinery accused of contaminating the ground water, if residents and/or the refinery disagreed with the executive agency enforcing the rules Congress wrote, they would contact their congressional representative and the issue could be adjudicated at a Congressional sub-committee level.

Sure, there is a lot of details that need to be filled in. But blame SCOTUS for that. Who is going to control this new process of filling in these details? The forces of corporate oligopolies or a representative democracy? It will be one or the other. Expanding the House and letting the administrative powers reside with Congress, gives us a chance to start over again. But additional reforms that create new political incentives for politicians to be more responsive to the voters and not special interests, is also required.

This would fundamentally redirect federal power to Congress in a time when many fear additional Executive overreach will be created by advocates of the Unitary Theory of the Presidency and the “clarification” regarding Presidential immunity. Uncapping the size of the House and moving the power to write the administrative rules governing the country to the House, will check the current and future power of the Executive. Just as the framers intended when they developed the concept of checks and balances.

Expanding Congress is an exceptionally bad idea. Look at the bottom of the barrel electeds currently in Congress. Imagine 3 times as many MTG/Gaetz/Bobert/Santos/etc as there are now. Aside from the logistics of where to put them all, the gridlock would be off the charts. And besides, handing power to “the forces of corporate oligopolies” IS what the corrupted SCOTUS intended.